60s of the XIX century The poor district of St. Petersburg, adjacent to Sennaya Square and the Catherine Canal. Summer evening. Former student Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov leaves his closet in the attic and mortgages to the old woman, the percent-lender Alena Ivanovna, who is preparing to kill, the last valuable thing. On the way back, he enters one of the cheap drinking rooms, where he accidentally meets with the drunken, lost official Marmeladov. He tells how the consumption, poverty and drunkenness of the husband pushed his wife, Katerina Ivanovna, to a cruel act - to send his daughter from her first marriage to Sonya to earn money on the panel.

The next morning, Raskolnikov receives from the province a letter from his mother describing the troubles suffered by his younger sister Dunya in the house of the depraved landowner Svidrigailov. He learns about the imminent arrival of his mother and sister in Petersburg in connection with the upcoming marriage of Duni. The groom is a prudent businessman Luzhin who wants to build a marriage not on love, but on the poverty and dependence of the bride. The mother hopes that Luzhin will financially help her son finish the course at the university. Reflecting on the sacrifices that Sonya and Dunya bring for the sake of those close to him, Raskolnikov is strengthened in his intention to kill the percussionist - a worthless evil "louse." Indeed, thanks to her money, “hundreds, thousands” of girls and boys will be delivered from undeserved suffering. However, the aversion to bloody violence rises again in the hero’s soul after a dream he remembered about his childhood: the boy’s heart breaks from pity for a nag that is beaten to death.

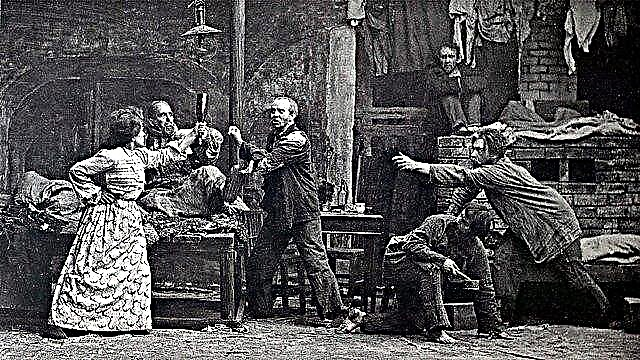

Nevertheless, Raskolnikov kills with an ax not only the “ugly old woman”, but also her kind, gentle sister Lizaveta, who unexpectedly returned to the apartment. Having miraculously gone unnoticed, he hides the stolen in a random place, without even evaluating its value.

Soon Raskolnikov with horror discovers alienation between himself and other people. Sick from the experience, he, however, is not able to reject the burdensome cares of his comrade at the University of Razumikhin. From the conversation of the latter with the doctor, Raskolnikov finds out that on the suspicion of murdering the old woman, the painter Mikolka, a simple village guy, was arrested. Painfully reacting to conversations about a crime, he himself also arouses suspicion among others.

Luzhin, who came on a visit, is shocked by the squalor of the hero's closet; their conversation grows into a quarrel and ends with a break. Raskolnikov is particularly offended by the closeness of practical conclusions from Luzhin's "rational egoism" (which seems to him vulgarity) and his own "theory": "people can be cut ..."

Wandering around St. Petersburg, a sick young man suffers from his alienation from the world and is ready to confess to a crime against the authorities, as he sees a man crushed by a carriage. This is Marmeladov. Out of compassion, Raskolnikov spends the last money on a dying man: he is transferred to a house, his name is doctor. Rodion meets Katerina Ivanovna and Sonya, who says goodbye to her father in an inappropriately bright dress of a prostitute. Thanks to a good deed, the hero briefly felt communion with people. However, having met his mother and sister in their apartment, he suddenly realizes himself “dead” for their love and roughly drives them away. He is lonely again, but he has a hope to get closer to Sonya, who has “crossed over,” like him, the absolute commandment.

Razumikhin takes care of Raskolnikov’s relatives, almost at first sight falling in love with the beautiful Dunya. Meanwhile, the offended Luzhin puts the bride before a choice: either he or the brother.

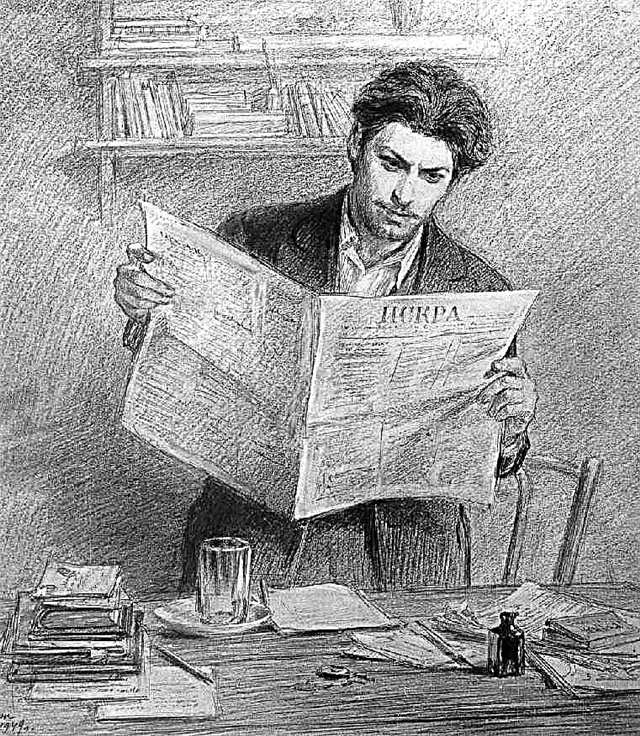

In order to find out about the fate of the things laid in the murdered woman, and in fact to dispel the suspicions of some acquaintances, Rodion himself asks for a meeting with Porfiry Petrovich, an investigator in the case of the murder of an old percent-raiser. The latter recalls Raskolnikov’s recent article on crime, inviting the author to clarify his “theory” of “two categories of people.” It turns out that the "ordinary" ("lower") majority is just material for the reproduction of their own kind, it is it that needs a strict moral law and must be obedient. These are "trembling creatures." "Actually people" ("higher") have a different nature, possessing the gift of a "new word", they destroy the present in the name of a better one, even if it is necessary to "step over" moral standards previously established for the "lower" majority, for example, shed someone else's blood. These "criminals" then become "new legislators." Thus, without recognizing the biblical commandments (“Thou shalt not kill,” “Thou shalt not steal,” etc.), Raskolnikov “authorizes” “the right of those who have it” - “blood of conscience.” Clever and insightful Porfiry unravels in the hero an ideological killer who claims to be the new Napoleon. However, the investigator does not have evidence against Rodion - and he lets the young man go in the hope that a good nature will defeat the errors of the mind in him and lead him to confess to the deed.

Indeed, the hero is increasingly convinced that he was mistaken in himself: “the real ruler <...> smashes Toulon, does the massacre in Paris, forgets the army in Egypt, spends half a million people in the Moscow campaign,” and he, Raskolnikov, is tormented by “vulgarity” "And the" meanness "of a single murder. Clearly, he is a "trembling creature": even after killing, he "did not step over" the moral law. The motives of the crime themselves double in the consciousness of the hero: this is a test of oneself for the "highest rank", and an act of "justice", according to revolutionary socialist teachings, transmitting the property of "predators" to their victims.

Svidrigailov, who came after Dunya to Petersburg, apparently guilty of the recent death of his wife, gets acquainted with Raskolnikov and notes that they are “of the same berry field”, although the latter did not completely defeat Schiller in himself. With all his disgust at the offender, Rodion's sister is attracted by his apparent ability to enjoy life, despite the crimes committed.

During lunch in the cheap rooms, where Luzhin, from economy, had settled Dunya with his mother, a decisive explanation took place. Luzhin is accused of slandering Raskolnikov and Sonya, to whom he allegedly gave money for base services selflessly collected by his impoverished mother to study him. Relatives are convinced of the purity and nobility of the young man and sympathize with Sonya’s fate. Exiled with shame, Luzhin is looking for a way to defame Raskolnikov in the eyes of his sister and mother.

The latter, meanwhile, again feeling a painful alienation from loved ones, comes to Sonya. She, who “crossed” the commandment “Do not commit adultery,” he seeks salvation from intolerable loneliness. But Sonya herself is not alone. She sacrificed herself for the sake of others (hungry brothers and sisters), and not others for herself, as her interlocutor. Love and compassion for loved ones, faith in God's mercy never left her. She reads Rodion gospel lines about Christ's resurrection of Lazarus, hoping for a miracle in her life. The hero does not succeed in captivating the girl with the "Napoleonic" idea of power over "the whole anthill."

Tormented by both fear and the desire to expose, Raskolnikov again comes to Porfiry, as if worried about his mortgage. It seems that an abstract conversation about the psychology of criminals ultimately leads the young man to a nervous breakdown, and he almost gives himself out to the investigator. It saves him an unexpected confession for everyone in the murder of the percussionist of the painter Mikolka.

In the passage room of the Marmeladovs, a commemoration of her husband and father is arranged, during which Katerina Ivanovna, in a fit of painful pride, insults the landlady. She tells her with the children to move out immediately. Suddenly Luzhin enters, living in the same house, and accuses Sonya of stealing a hundred-dollar bill. The "guilt" of the girl is proved: money is found in the pocket of her apron. Now, in the eyes of those around her, she is also a thief. But suddenly there is a witness that Luzhin himself quietly slipped a piece of paper to Sonya. The slanderer is confounded, and Raskolnikov explains to the audience the reasons for his act: having humiliated his brother and Sonya in the eyes of Duni, he hoped to return the bride’s location.

Rodion and Sonya go to her apartment, where the hero confesses to the girl in the murder of an old woman and Lizaveta. She regrets him for the moral torment to which he condemned himself, and offers to atone for guilt by voluntary confession and hard labor. Raskolnikov, however, laments only that he turned out to be a "trembling creature," with a conscience and a need for human love. "I will still fight," he does not agree with Sonya.

Meanwhile, Katerina Ivanovna with the children is on the street. She begins with throat bleeding, and she dies, refusing the services of a priest. Svidrigailov present here undertakes to pay for the funeral and provide children and Sonya.

At home, Raskolnikov finds Porfiry, who convinces the young man to confess: the "theory", which denies the absoluteness of the moral law, rejects from the only source of life - God, the creator of a single by nature humanity - and thereby condemns his captive to death. “You now <...> need air, air, air!” Porfiry does not believe in the guilt of Mikolka, who “accepted suffering” because of the primordial popular need: to atone for the sin of inconsistency with the ideal - Christ.

But Raskolnikov still hopes to "step over" and morality. Before him is an example of Svidrigailov. Their meeting in the inn reveals the sad truth to the hero: the life of this "most insignificant villain" is empty and painful for himself.

Reciprocity of Duni is the only hope for Svidrigailov to return to the source of being. Convinced of her irrevocable dislike for herself during a stormy conversation in his apartment, he shoots himself in a few hours.

Meanwhile, Raskolnikov, driven by the lack of "air", says goodbye to his family and Sonya before recognition. He is still convinced of the fidelity of “theory” and full of contempt for himself. However, at Sonya’s insistence, before the eyes of the people he repentantly kisses the earth before which he “sinned”. In the police office, he learns about the suicide of Svidrigailov and makes an official confession.

Raskolnikov finds himself in Siberia, in a penal prison. Mother died of grief, Dunya married Razumikhin. Sonya settled near Raskolnikov and visits the hero, patiently bearing down his gloom and indifference. The nightmare of alienation continues here: convicts from the common people hate him as "atheist." On the contrary, they treat Sonya with tenderness and love. Once in a prison hospital, Rodion sees a dream reminiscent of paintings from the Apocalypse: the mysterious "trichins", dwelling in people, give rise to a fanatical conviction in each one of one's own rightness and intolerance of the "truths" of others. "People killed each other in <...> senseless malice" until the entire human race was destroyed, except for a few "pure and chosen ones." He finally reveals that the pride of the mind leads to discord and death, and the humility of the heart leads to unity in love and to the fullness of life. It awakens "endless love" for Sonya. On the threshold of “resurrection into a new life,” Raskolnikov picks up the gospel.