The action takes place in 1890-1918. The work is written in the form of memories of the author about his peer, a young English officer who died in France at the very end of the First World War. His name appeared on one of the last lists of those who fell on the battlefield when hostilities had long ceased, but the newspapers still continued to publish the names of those killed: "Winterborn, Eduard Frederick George, captain of the second company of the ninth battalion of the Fodershire Regiment."

George Winterborn believed that his possible death would hurt four people: his mother, father, wife Elizabeth and Fanny's mistress, and therefore their reaction to the news of his death would hurt his pride, although at the same time it would alleviate his soul: he would understand that in this life he had no debts left. For the mother, who spent time in the company of another lover, the tragic news was just an excuse to act out as a heartbroken woman to provide her partner with the opportunity to console herself by satisfying the sensations triggered by a sad event. The father, who by that time had gone bankrupt and went into religion, seemed to have lost interest in everything worldly - when he learned about the death of his son, he began to pray even more earnestly, and soon he himself went into another world, hitting a car. As for his wife and mistress, while George fought in France, they continued to lead a bohemian lifestyle, and this helped them quickly console themselves.

It is possible that, having become entangled in personal problems, tired of the war, on the verge of nervous exhaustion, George Winterborn committed suicide: after all, a company commander does not have to fire a bullet in his forehead - it is enough to rise to his full height under machine-gun fire. “What a fool,” said the colonel about him.

Then the events in the novel return almost three decades ago, to the time of the youth of George Winterbourne Sr., the father of the protagonist, who came from a prosperous bourgeois family. His mother, an imperious and wayward woman, crushed all the rudiments of masculinity and independence in her son and tried to tie her to her skirt more firmly. He learned to be a lawyer, but his mother did not let him go to London, but forced him to practice in Sheffield, where he had almost no work. Everything went to the point that Winterbourne Sr. will remain a bachelor and will live next to the dearest mother. But in 1890, he made a pilgrimage to the patriarchal Kent, where he fell in love with one of the many daughters of the retired captain Hartley. Isabella conquered him with her liveliness, bright blush and catchy, albeit a little vulgar beauty. Imagining that the groom was rich, Captain Hartley immediately agreed to the marriage. George’s mother didn’t particularly mind, perhaps deciding that tyranny of two people was much nicer than one. However, after the wedding, Isabella immediately faced three bitter disappointments. On the wedding night, George was too inept and grossly raped her, causing much unnecessary suffering, after which she tried all her life to minimize their physical intimacy. She experienced a second blow at the sight of the ugly little house of the "rich." The third - when she found out that her husband's law practice does not bring a penny and that he is dependent on his parents, who are unlikely to be much richer than her father. Disappointment in married life and constant mother-in-law nit-picking forced Isabella to turn all her love on first-born George, while his father spat on the ceiling in his office and vainly urged his mother and wife not to quarrel. The final collapse of the practice of George Winterbourne Sr. came when his former classmate, Henry Balbury, having returned from London, opened his own law firm in Sheffield. George, it seemed, was only glad for this - under the influence of conversations with Balbury, the unfortunate lawyer decided to devote himself to "serving literature."

Meanwhile, Isabella's patience snapped, and she, taking the child, fled to her parents. The husband who came for her was met by the outraged Hartley family, who could not forgive him for not being rich. Hartley insisted that the young couple rent a house in Kent. As compensation, George was allowed to continue his "literary work." For some time, the young ones were blissful: Isabella could twist her own nest, and George could be considered a writer, but soon the financial situation of the family became so precarious that only the death of George's father, who left them a small inheritance, saved them from the catastrophe. Then the trial of Oscar Wilde began, finally turning Winterbourne Sr. away from literature. He again took up the practice of law and soon became rich. She and Isabella had several more children.

Meanwhile, George Winterbourne Jr., long before he was fifteen years old, began to lead a double life. Having understood that the true soul movements should be hidden from adults, he tried to look like a healthy savage boy, used slang words, pretended to be interested in sports. And he himself was sensitive and delicate in nature and kept in his room a volume of Keats’s poems stolen from his parents' bookcase. He was happy to draw and spend all his pocket money on the purchase of reproductions and paints. At the school, where they attached particular importance to sports successes and military-patriotic education, George was on a bad account. However, some even then saw in him an extraordinary nature and believed that "the world will still hear about him."

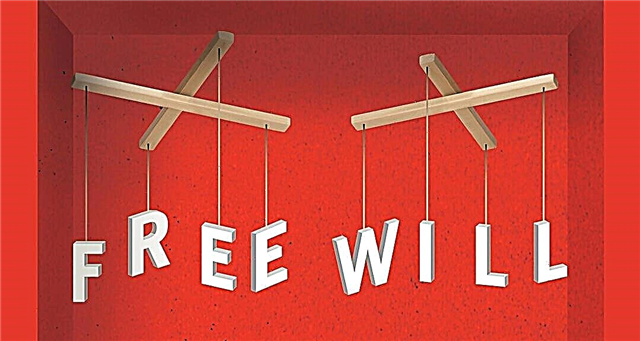

The relative well-being of the Winterbourne family ended on the day when his father suddenly disappeared: having decided that he had gone broke, he fled from creditors. In fact, his affairs were not so bad, but the flight destroyed everything, and at one moment the Winterbourne turned from almost rich to almost poor. Since then, his father began to seek refuge in God. The family has a difficult atmosphere. Once, when George, returning home late, wanted to share joy with his parents - his first publication in the magazine - they attacked him with reproaches, and in the end, his father told him to leave the house. George went to London, rented a studio and began painting. He made a living mainly from journalism; he made extensive acquaintances in a bohemian environment. At one of the parties, George met Elizabeth, also a free artist, with whom he immediately established a spiritual and then physical affinity. As passionate opponents of the Victorian foundations, they believed that love should be free, not burdened by lies, hypocrisy and forced obligations of fidelity. However, barely Elizabeth, the main champion of free love, had suspicions that she was expecting a child, as she immediately demanded to register the marriage. However, the suspicions turned out to be in vain, and nothing has changed in their lives: George remained in his studio, Elizabeth in his own. Soon, George got married with Fanny (more on the initiative of the latter), and Elizabeth, still not knowing about this, also found a lover and immediately told everything about George. Then he should have confessed to his wife in connection with her close friend, but on the advice of Fanny he did not do this, which he later regretted. When the “modern” Elizabeth learned of “betrayal,” she quarreled with Fanny and her relationship with George also began to cool. And he darted between them, because he loved both. In this state, their war found them.

Entangled in his personal life, George joined the army as a volunteer. He experienced the rudeness of non-commissioned officers, drill in the training battalion. Physical deprivation was great, but moral torment was even harder: from an environment where spiritual values were put above all, he ended up in an environment where these values were despised. After some time, he was sent to France on the German front as part of the engineer battalion.

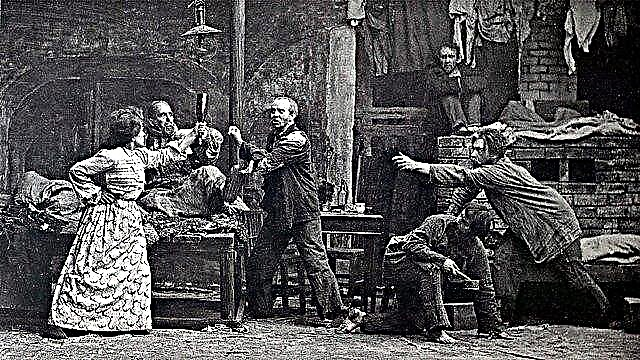

In winter, calm reigned in the trenches: the soldiers of the opposing armies fought with one enemy - the cold; they suffered from pneumonia and tried in vain to warm themselves. But with the onset of spring, fighting began. Fighting on the front line, George was a dozen times from death - fell under the fire of enemy batteries, was subjected to chemical attacks, participated in battles. Every day he saw death and suffering around him. Hating the war and not sharing the cheers-patriotic moods of his comrades in arms, he nevertheless honestly performed his military duty and was recommended to the officer school.

Before starting classes, George received a two-week vacation, which he spent in London. It was at that moment that he felt that he had become a stranger in the once familiar environment of metropolitan intellectuals. He tore his old sketches, finding them weak and studentish. I tried to draw, but could not even draw a confident pencil line. Elizabeth, infatuated with her new friend, did not pay much attention to him, and Fanny, who still considered George a wonderful lover, also had difficulty cutting out a minute or two for him. Both women decided that he had been greatly degraded since he joined the army, and everything that was attractive about him died.

At the end of the officer school, he returned to the front. George was saddened by the fact that his soldiers were poorly trained, the position of the company was vulnerable, and his immediate superior had little sense in military craft. But he again harnessed himself to the strap and, trying to avoid unnecessary losses, led the defending company, and when the time came, he led her on the offensive. The war was coming to an end, and the company was fighting its last battle. And when the soldiers lay down, pressed to the ground by machine-gun fire, Winterborn thought he was losing his mind. He jumped up. A machine-gun burst hit him on the chest, and everything was swallowed by darkness.